Over the last 6 months or so, I’ve been tracking my Youtube usage. I came to discover that I was spending on average about an hour a day watching YouTube videos. While there are a lot of things I love about YouTube, it comes with some negatives. So, for one month, I gave up YouTube.

Admittedly, at times I missed watching videos online, especially comedy and some news updates, but largely I found life better without YouTube than with it. It showed me just how complicated one’s relationship can be with technology and various digital services. YouTube and many other services are designed to hook us and keep us using them. They are designed to be addictive. Sadly, as of now, we can’t adjust these technologies to fit our ideal way of using them either.

30-day challenges are a great way to experiment with something in your life. Month-long challenge is largely about discovery and are burdensome than full-on goals or building new habits. By trying something out for a month, you can figure out if it’s something you want to continue going forward.

Most of the routines I now have started as short trials or challenges, like running, daily morning pages, and time tracking. I’ve done a number of month-long experiments over the years, and I am especially a fan of tracking them too. In fact, some of my 30-day challenges were tracking-specific challenges, like what I did with mood tracking and tracking my bowels.

I had a couple motivations for this 30-day No YouTube challenge. The first was to spend less time binge watching random online videos and more time reading, writing, and other personal projects. I figured I’d lose out on some amount of news and content, but that seemed okay to me. I hypothesized that an extra 8 hours a week would mean more books and articles read and possibly a bit more time on the computer. Basically, the main thing I expected to see a big difference in my time logs and media usage. This wasn’t exactly what I find.

Like any technology, YouTube has its pro’s and con’s. Experiments like these provide a good way to figure out what works for you.

In this post, I want to share about about my month-long No YouTube challenge. To give a bit of context, in the first part, I’ll talk about what is a 30-day challenge and some of the benefits of this kind of short-term discovery type of goal. After that, I’ll briefly share how and why I did one on YouTube Watching. We will then dig into the my data and tracking logs to figure out what what changed (and what didn’t!) over the last month. Finally, I’ll conclude with some general observations on the challenge, technology, and if and how I’ll use YouTube going forward.

NOTE: If you are interested in tracking your YouTube usage, I’ve written a complete guide to YouTube Tracking.

What is a 30-day challenge? And Why Do Them?

Goals and goal-setting are some the most effective cognitive strategies we can use for behavior change. As I’ve talked about in my on-going series on the science of goals, goals exist as a multistage pursuit wherein among other elements you have the goal intention or goal-setting, which refers to what you want to achieve, and the goal pursuit or goal striving, which are the actions you take in pursuit of that goal.

Much of research on goals focused on one of these two ends, either goal-setting or the goal pursuit and different strategies you can use. Goal Setting Theory (GST) has shown that how you set goals modifies your performance and demonstrated that harder, more specific goals are more effective than vague or easy goals. When comes to the goal pursuit itself, two effective techniques are mental contrasting and implementation intentions (if-then plans).

A 30-day challenge is a slightly different kind of goal. The main point is to try something new for awhile and figure out if it works for you or not. The intention should be one of discovery and learning, rather than expecting to develop a new habit in such a short amount of time. In fact, a good amount of research indicates that most habits take more than 30 days to develop.

Also unlike the science of goal-setting that focuses on longer-term objectives and harder challenges, 30-day challenges are generally less ambitious and come with less of an obligation too. They are, by design, less of an automatic thing you do and more of a scheduled or willed action we are experimenting with. A few good examples of 30-day challenges are reading daily, giving up caffeine, exercising for 30 minutes, or writing in a journal. Basically, you try it for a while and see if you like it.

All things considered, 30-day challenges can can still can be an excellent way to figure out of if a certain lifestyle change, technology, or something else is right for you. Or, like my example, if life without a certain technology is right.

One of the best things about 30-day challenges is they take place almost entirely within the “honeymoon” period, meaning it feels new and fresh, so your curiosity and openness get peaked. Their shorter nature makes you more conscious and observant too. They encourage us to track (especially fitness or reading challenges) and often times you’ll find yourself aware of the changes.

The natural way a month challenge fits with our calendars is a good thing too. There is a a nice rhythm to them. You get sparked by a new month to try it, and as the month comes to an end, you organically become reflective.

Whether or not you are a hardcore tracker or into quantified self like me, once completed 30-day challenges are generally pretty easy to do a comparison. All you have to do is look at the previous month or two, and ask yourself what changes you felt over that period. If you have tracking logs a simple before and after comparison should be enough.

My advice when it comes to month-long challenges is to first a list of all the things you want to try at some point. Then pick one and do it for a month. Don’t make them too hard at the beginning. If you want to take advantage of the science of goals, then make a bit of extra effort to define your goal better so that it is tied into a trigger. So, for example, if you want to exercise daily, you should set your goal something like this:

After getting home from work, I’ll go for a run or workout at the gym. If it’s after 9pm and I realize I haven’t exercised yet today, then go for a short 15 or 20 minute walk around the neighborhood or a quick session of stretching or yoga.

This sort goal setting is called implementation intentions or more informally if-then plans. There is a lot of strong research showing the effective of these cognitive strategies at following through on our goals and habits (Gollwitzer & Sheeran, 2006; Gollwitzer, 1999). Essentially what you are doing is mentally linking an activity with a situation or trigger. So when that situation arises, you will simply do that act rather than thinking about it or deploy willpower to force yourself.

There are other cognitive strategies you can use, like blocking out the time in your calendar, finding a buddy to work on the challenge together, or using a goal tracker. Since the action is likely new, I find a habit tracker to be the best way to ensure I stick to the new routine.

Now that we’ve looked at what is a 30-day challenge and some of its benefits, let’s take a look at my recent experiment.

My 30-Day No YouTube Challenge

“Nobody exists on purpose, nobody belongs anywhere, everybody’s going to die. Come watch tv.”

Rick from the TV show, Rick and Morty.

I’ve been a regular user of YouTube for a long time. The platform gives me targeted content for free anytime anywhere I want it, which is great. There are tons of educational videos, and content that makes me laugh, smile and think. I’ve used the platform to learn about statistics, economics and data science. It’s also where I can to ponder the Philosophy of Rick and Morty.

But let’s be honest. YouTube is a channel that delivers entertainment sandwiched between advertising. It’s objective is to maximize the amount of time you spend on it so they can maximize your exposure to ads. By most accounts, YouTube is one of the most successful online platforms in the so-called attention economy.

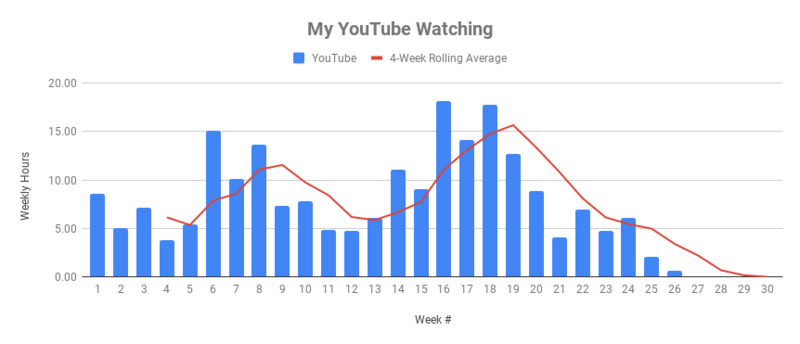

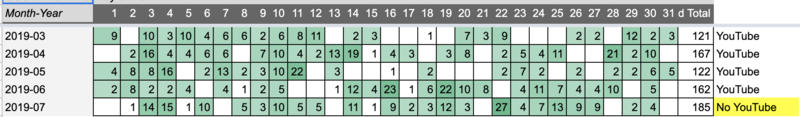

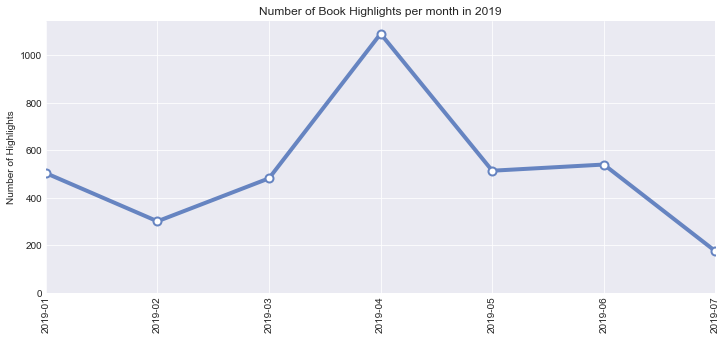

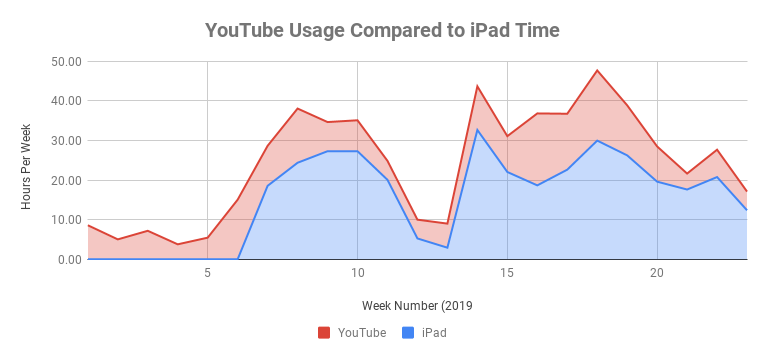

As I share in my Guide to YouTube Tracking, there are a few ways to track your usage. Personally, I track it once a week by opening up the YouTube app where there is a time report and manually logging my weekly YouTube time into my data-driven weekly review spreadsheet. Here is a breakdown of my recent usage:

The big negatives for me with YouTube are the time suck, addictive tendency, binge usage, high arousal, and sleep loss. I also find it occasionally acts as an emotional retreat, when I’m feeling lonely or a little depressed. Basically, periodically I binge a bunch of videos in a long session, and this tends to happen when I’m a bit off. Unfortunately, this tends to result in not going to bed on time and less sleep only makes it worse.

Moreover when I travel, I sometimes fall into some bad habits. One of those habits is YouTube binging. It happens when I’m not traveling too. I don’t have a specific count of how often, but my guess it happens roughly every week or two where I end up not going to bed at a good time and spending 3 to 4 hours straight watching endless series of videos on YouTube. While it might start off as educational, it often ends up being a lot of time for not much gained.

Coming back home after roughly a month of travel, I decided it might be interesting to take a break. Inspired by another tracking buddies monthly challenges, I did my own: 30 Days without YouTube.

Going into my YouTube Free Month, I had already spent roughly 213 hours on YouTube this year. I was averaging 8 hours and 53 minutes a week, which equated to 1 hour and 16 minutes per day. Like it or not, that’s a lot of time.

Setting up this challenge wasn’t hard I simply deleted the YouTube apps on all my devices. Since I don’t use YouTube on the computer, this was enough to stop me not from using it.

Interestingly, initially I had these habitual moments in the evenings and at breakfast where I felt the urge to watch a video. Like or not, I’d created triggers in my day where I watched YouTube. Fortunately, after a few days my habits changed, and I didn’t really notice it. I turned on some music at breakfast, watched the news on TV or did a bit of light reading. Being a constant learner, I generally don’t struggle to find ways to occupy my mind. I just needed to a new medium.

So, it’s been a month now. What changed and what didn’t? What does the data say?

Data Analysis: Things That Didn’t Change

Interestingly my data didn’t quite look like I expect it to.

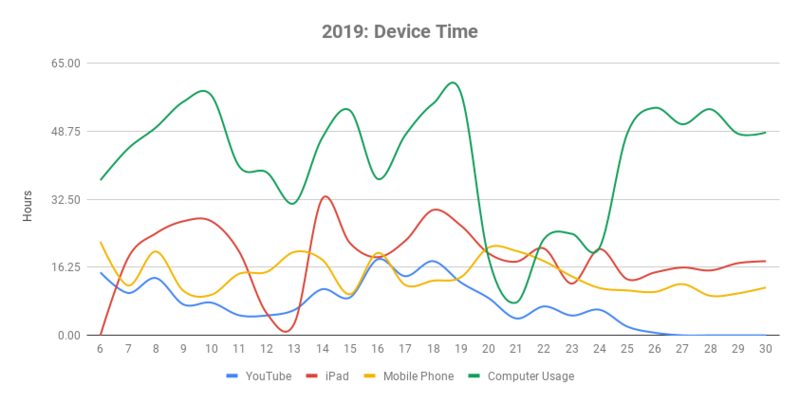

Here are a couple of charts that attempt to put this month in perspective, based on my device usage and a few other parameters I track:

Weekly Time on Devices: No Major Changes in Phone and Tablet Usage

NOTE: Additional device data I added to my my data-driven weekly review include ScreenTime from iPhone and iPad. My computer usage comes from RescueTime.

This device usage chart shows variation due to up and down work and travel. I work in various creative and professional sprints too.

Heatmap of Articles Read in Recent Months, According to Instapaper

NOTE: I generated this using the Instapaper and its integration with IFTTT. Data was stored into a Google Sheet and I used a pivot table with some conditional color formatting to make it look like a heatmap.

This articles read chart shows an increase in article read during this challenge, but it wasn’t markedly different from the overall trajectory.

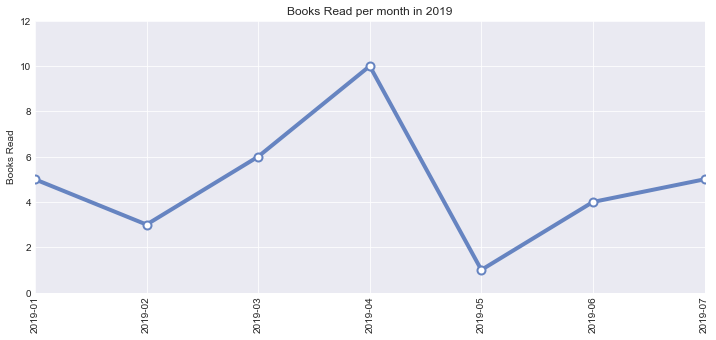

Kindle Highlights Per Month: Less Highlights

NOTE: I used QS Ledger with its Kindle parser and data visualization scripts to get my kindle highlights and generate this report.

While I expected to see a lot more highlights in my Kindle logs, this isn’t what happened. In fact, it was lower than almost any month so far this year.

Monthly Books Read, According to Goodreads

NOTE: I used QS Ledger and the Goodreads integration to collect my books read and reviews and then generate this report.

When it comes to books read, I did finish several books over the month, but it was about average for me (roughly a book a week).

Initial Conclusions:

My original hypothesis was that I expected to see some noticeable changes in my media and computer, but from looking at the charts, here is what I found:

- Computer usage was close to average.

- Project time was nearly same too.

- Article reading was only a little bit higher than average and aligned with recent months’ growth.

- I finished 4 books or about a book a week, which was typical.

This meant that my month without YouTube didn’t result in me working more nor was I reading more either (or so it seemed). So what happened?

Data Analysis: So, what changed?

The lack of changes in the the areas I expected to change was curious. By my own reckoning I didn’t watch TV or movies much more, and it seemed like I wasn’t reading more either, in spite of having an extra 8 hours a week free now.

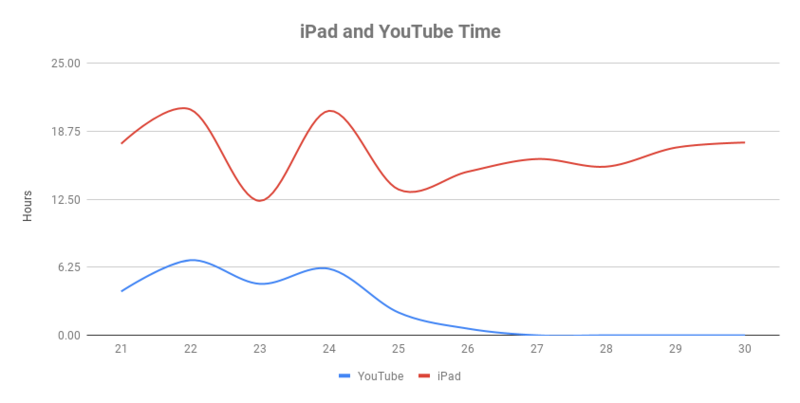

When I re-looked at my device usage logs, I noticed something interesting with my iPad usage numbers:

If you look at the trends we can see a pretty close correlation between iPad usage and YouTube time. This is not surprising since I almost exclusively watch YouTube on my tablet. But when you look at recent weeks AFTER I stopped using YouTube, you’ll notice that my tablet time remained steady and even went up slightly:

This is where more detailed screentime logs would be really helpful. Unfortunately, on an iOS device, there is no simple way to get detailed logs of time usage in the actual applications. Right now I just manually log the total time. So, to tease out my recent changes, the best we could do was look at a recent week.

In Screentime, here is what I found:

- Files 9h29

- Instapaper 3h 49

- Safari 3h 9m

- Spotify 1h 8m

This is our first clue. It is finally becoming clear that my YouTube time on the tablet was replaced by reading PDFs. I wasn’t reading more books or more online articles; I was reading more PDFs!

SIDEBAR: Tracking PDF Reading

As far as I know, there is no perfect or complete way to track your PDF reading. I’ve got two options I can use to tease out a bit more intel on my PDF reading changes.

The first way is a PDF tracking hack I came that uses a bash script to keep a daily log of changes in the directories where I store PDFs. You can find and try out the code here: https://gist.github.com/markwk/bd9e0b109110a943d32548291e91a241. The main focus is on tagged PDFs, and it does provide a good starting point. Right now the script is collecting various data, but I have yet to write any code to do the needed analysis. Unfortunately, a full data analysis is outside the scope of this experiment too.

The second way to track my PDFs involves a little workaround using how I read and process PDFs. For me, I mostly read PDFs on my Tablet with the Preview App, where I make various highlights. Once I’m finished I tag the PDF in Green, and then, on my Mac, I can use the Skim App to export those highlights.

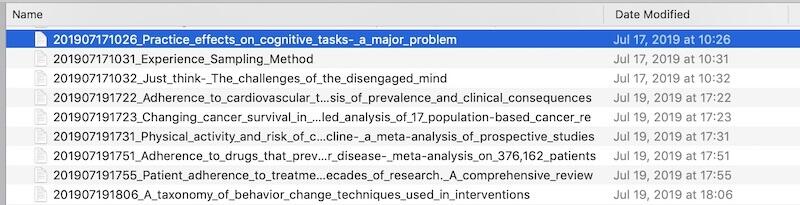

After exporting the highlights, I append the file’s date time. This results in a directory with files that look like this:

With a bit of command line parsing, it isn’t hard to count the file numbers by date.

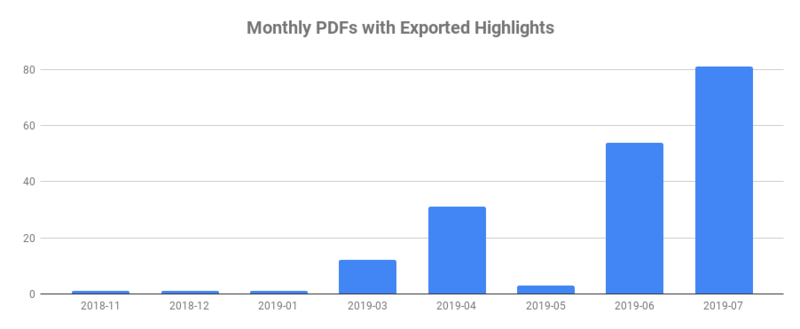

Tracking PDF Reading According to Exported Highlights

Here’s a portrait of total PDFs read in terms of the PDF files where I exported highlights:

This obviously isn’t an exact representation of my PDF reading. I’ll need to use other tracking data at another point to get a better number. But it still shows what we were looking for: a noticeable increase in PDFs that were exported in July.

This is the second clue into how my behavior changed without YouTube in the last month: I read more PDFs and exported more highlights.

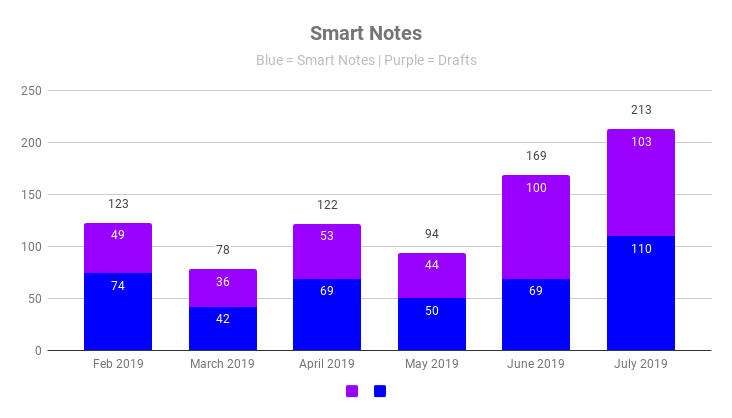

More Smart Notes

The third datapoint and clue came from looking at my smart notes. Awhile back I changed how I take notes. The key aspect is about having a productivity and knowledge management system I can depend on in my learning and creative endeavors. There are a lot of technical ways you can set up this kind system. I use plain text files since it makes it easy to track my notes too, but a tool like Evernote and many others could be tweaked for similar usage.

Looking at my high-level note logs, we see another change: I took more notes!

So, while I didn’t spend that much more time on my computer or on projects, less YouTube time did translate into more time spent on creating smart notes which were largely based on my increased PDF reading.

Even though I vaguely knew I was reading more PDFs in the last month, it wasn’t until I dug into my logs that I was able to calculate the difference. By my rough ballpark estimate, I spent about 35 to 40 some hours reading PDFs on my tablet. A bit more than normal but not that surprising consider I wasn’t watching YouTube and I wasn’t reading more on my Kindle.

Let’s jump into a few of my conclusions.

Conclusion: Better Without It Than With It?

Since most habits take more than a month to develop, 30-day challenges are a special kind of goal that should aim for discovery and self-understanding. They exist to help you to learn something new or to figure out whether a new habit is right for you. If that short-term change fits your needs, you can work on developing it more over the coming months by converting it into a bigger goal. You might even use something like a goal tracker to help you get get there.

In my opinion, the end point of most bigger goals should be about developing new routines. Good habits are one of of the best investments of your time, especially healthy, productive and creative ones. This is due to how they create a permanent and automatic way of life you can use forever. It’s also why bad habits can be so detrimental too. Even though goals are a great thing, self-improvement should not be a forever endeavor. Instead, forget about willing yourself to better and focus on goals that build habits and routines that make good living easy.

There are a lot of great options for month-long challenges, like daily exercise, a gratitude journal, giving up social media, going caffeine free, or working on a hobby among many other. I’m admittedly partial to tracking experiments, so if you’ve never tried tracking, give self-tracking a try for a month and see what you can discover and learn. Check out one of my tracking guides if you need any tips.

For my recent challenge, I decided to go a month without YouTube. I’m not sure if I classify as a heavy or average user, but an hour a day seemed a bit much for me. Especially when you think about it as nearly 5% of a 168 hour week or nearly 8% of my awake time.

As a long-time self-tracker and someone actively trying to use technology towards self-improvement, this month without YouTube made me realize a few things. For me, one of the biggest lessons I realized from this experiment was that I can live without YouTube. In fact, it was nice without it.

In many ways YouTube provides an incredible service: endless and largely free videos anytime anywhere I want them. They are also really good at delivering mostly good stuff but with variable returns of really good content. According to neuroscience, this variability of reward makes it highly addictive through how it modulates our dopamine levels among other factors. I was, for lack of a better word, addicted to YouTube.

When I first started my month without YouTube, I found in myself weird automatic tendencies. There were moments where I felt an urge to watch some YouTube. It was a habit that got triggered in certain situations in my day. It’s clear that technologies like YouTube can be effective at changing us. It had changed me. I now some of these triggers and have effectively put in alternative behaviors.

After a month without it, I’m glad that the urge for YouTube is gone. It’s good to know that this kind of addiction wasn’t permanent. All in all, I most missed the comedy videos, and I haven’t found a good way to replace those. Being away from the news cycle was fine for awhile, and something I should be willing to do more regularly. On the educational side, it was hard at a few points where I knew a YouTube video would give me the knowledge I needed and not having access to it could be frustrating. Fortunately, there are plenty of books and articles too on nearly any topic, so educationally lack wasn’t that bad.

So, will I be back on YouTube watching anytime soon?

For now, I don’t plan to immediately start using YouTube again. Overall, I found better ways to spend my time without the time suck and addictiveness of YouTube.

Ultimately, the main question this challenge left me with was this: Can we find balance in our usage of certain technologies? Or we stuck with all or nothing?

There are a lot of discussions around how addicted we are to our phones, social media and TV. Some even link increased phone usage with depression, social unease, and worsening health, especially in the so-called iGen Generation (Twenge, 2017). Along with social media apps and Netflix, YouTube owns a key portion of many people’s time and attention.

Time limits and logs are a great addition in the technology space. It’s great that both YouTube and my device provide these stats. These numbers can help you get a grip on your usage. Unfortunately, while I don’t have data to back this up, I suspect that the current implementation of time limits fails for many like me. I believe this is due to how they act as warning but fail to deploy richer cognitive strategies for behavioral change (Carey, 2018; Michie, 2013). Technology companies doesn’t actually want to help us live better with technology; they merely feel obliged to make an altruistic gesture.

When it comes to YouTube, if I could limit it to a pure educational tool or better tweak it, I might switch back to it more whole-heartedly. I’d like to be nudged off of using it sometimes. I’d like more control and less feeling entrapped somehow. I’d like it to be tailored to my digital life objectives. For example, I’d like to be able to watch one video without being sucked into ten.

Ultimately, what I’d like to see one day are apps and services that allow us to make the adjustments needed for managing healthier usage. Too many apps and services are dedicated to and designed for capturing your full attention for as long as possible. As a technologist and app developer, I realize much of this is due to the business models behind these “free” services. I would love to have apps that provide value and goodness for a period of my choosing but without ensnaring us for as long as they can keep us. I want tools that align to a conscious usage, rather than some kind of debilitating enslavement.

I know it’s it’s a pipe dream, and until we get there, it seems there were always be trade-offs in the technologies we incorporate into our lives. Sometimes we are better off a service than on it. In the case of YouTube, I think I’m off, off.

What about you? What technologies are you wondering if you are better off of than on?

References:

- Carey, R. N., Connell, L. E., Johnston, M., Rothman, A. J., de Bruin, M., Kelly, M. P. et al. (2018). Behavior change techniques and their mechanisms of action: a synthesis of links described in published intervention literature. Annals of Behavioral Medicine.

- Gollwitzer, P. M. (1999). Implementation intentions: strong effects of simple plans. American psychologist, 54(7), 493. Retrieved from http://kops.uni-konstanz.de/bitstream/handle/123456789/10101/99Goll_ImpInt.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Gollwitzer, P. M., & Sheeran, P. (2006). Implementation intentions and goal achievement: A meta-analysis of effects and processes. Advances in experimental social psychology, 38, 69-119.

- Michie, S., Richardson, M., Johnston, M., Abraham, C., Francis, J., Hardeman, W. et al. (2013). The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Annals of behavioral medicine, 46(1), 81-95.

- Twenge, J. M. (2017). Have smartphones destroyed a generation. The Atlantic, 3. Available online at https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2017/09/has-the-smartphone-destroyed-a-generation/534198/.