Where is the lightning to lick you with its tongue? Where is the frenzy with which you should be inoculated? Behold, I teach you the overman: He is this lightning; he is this frenzy. – Friedrich Nietzsche (quoted in Rise of Superman by Steven Kotler)

Flow is a mental state in which we are so engrossed in a challenging or enjoyable activity that nothing else matters.

In flow, we experience what might be called energized focus and often witness forms of peak mental and physical performance. Basketball players can’t miss a shot, a rapper’s words flow effortlessly or a conversation enfolds magically are all examples of flow or feeling “in the zone.”

Flow is an experience found in mountain climbers, writers, slackliners, artists, athletes, coders, sex, and many other professions. But it is also a mental state that can be found in everyday life activities too, like learning or an engaging discussion.

Flow is most consistently found when we do things that require our peak abilities. When the task is too easy, we feel lethargy and boredom. When the challenge is way too hard, we panic and stress out. But when the challenge is just hard enough, we are forced to engage our fullest capacities. This push to perform at the limits of our ability makes us feel alive and engaged. In flow, we often feel enjoyment, pleasure, and happiness.

There are evolutionary reasons why flow matters. Flow initiates a series of neurochemical changes that heighten our senses and increase our cognitive and motor skills. Flow makes us more capable of surviving when threatened, solving pressuring problems and dealing with challenges as an individual and in a group.

Not only is this same mental state primed and better for survival, creativity and peak performance; it’s also ideal for learning too. In fact, learning and creative activities like painting and writing are two examples where both masters and apprentices can experience a state of flow.

I’ve been interested in flow for some time, both from the side of improving how I optimize my learning and creativity as well as how one might track and quantify such momentary, subjective states. A few guiding books for me on flow have been Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Rise of Superman by Steven Kotler, and Experience Sampling by Joel M. Hektner. I’ve also found some of the elements of flow in the book by Cal Newport and concept called Deep Work.

Through these books and my own self-experimentation, I’ve come to realize just how powerful this mental state can be and I’ve come to organize my time, my life and my work around it. I also see flow as something a strong proxy for the benefits of biohacking, certain neuroenhancements and even aspects of transhumanism. Flow has served us for evolutionary history and will continue to serve as venture into space, combat diseases, and become more intertwined with technology and machine learning.

In this post, lets look at what is flow and why it matters for us as humans in the past, today and in future. Hopefully through an understand of flow, we can see why, as creatives, learners, peak performers and pursuers of excellence, we should look for flow as a key element in human flourishing.

NOTE: This post is the first part of two part series on flow. See Part 2 for a dive into how to track flow.

What is Flow?

In psychology and in our own observed lives, we experience and recognize a number of states of consciousness. The most obvious division is between wakefulness and sleep. But even there we start to notice in-between states too. For example, there is the weird half-awake, half-asleep state as we are falling asleep or waking up. This transition phase is called the hypnagogic and as its own unique subjective state and brain chemistry. During sleep, we also dream, and some people can also become lucid and can take control of their dreams. In short, consciousness isn’t simply an on-off switch between awake and asleep.

In fact, as Jeff Warren shows in his wonderful book, Head Trip, the “wheel of consciousness,” as he calls it, has at least 12 recognizable and scientifically demonstrated states. Noticeably for our purposes, Warren includes one separate state he labels “the zone.”

While going by a few different names, flow has been studied by various researchers for a long time, including by William James who might be called the father of modern psychology and more recently by contemporary psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi.

The roots of the concept of “flow” can be seen way back in William James’ idea of “mythical experience” (1902) and Maslow’s “peak performance.” Maslow studied exemplars of human performance and saw high achievers are intrinsically motivated and fall into intensively focused activity:

“During a peak experience the individual experiences an expansion of self, a sense of unity, and meaningfulness in life. The experience lingers in one’s consciousness and gives a sense of purpose, integration, self-determination and empathy.”

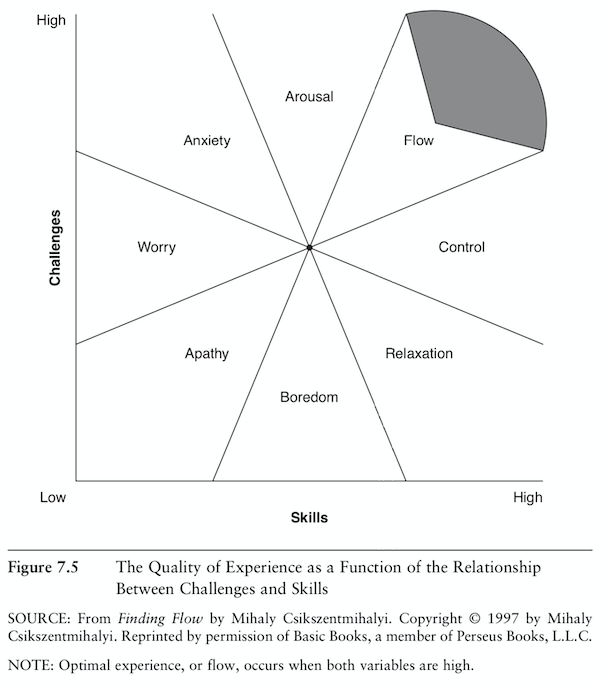

According to Csikszentmihalyi, a former professor at University of Chicago and one of the chief psychological researchers into flow, flow comes from deploying our peak skills in near peak challenges.

For him, flow emerges when we are in defiance against an obstacle at close to the limit of our abilities. These situations, often scary, sometimes life-threatening, require the best of us. Less challenging situations and not using our skills to their fullest will result in apathy and boredom or when an obstacle surpasses our skills, we become anxious and worried.

Peak challenges combined with deploying our peak mental and physical capacities, according to Csikszentmihalyi, result in flow.

Operational Definition for Flow

Flow-y situations come from peak challenges at the limit of our skills

Through a research methodology called Experience Sampling (which we will explore separately here), Csikszentmihalyi found among various populations a correlation between the type of activities people are engaged with and the mental states. Specifically, people were in flow and happier when they did activities that were challenging and required them to deploy their skills at their fullest.

This has lead to what might be called an operational definition of flow: Flow is what results from situations where people perceive the challenge as high (but not too hard) and posses and deploy their skills at their highest ability (but not too high to be beyond their skillset).

Put another way:

Inducing flow is about the balance between the level of skill and the size of the challenge at hand (Nakamura et al., 2009).

Flow is a state where you feel in control over the tasks at hand, even when they are hard and challenging.

This rule of inducing flow or peak performance is sometimes calls the Yerkes-Dobson law where performance increases with physiological or mental arousal, but only up to a point. As stress increased, performance improves until you reach a certain limit and levels drop off or decline.

Shorthand for this would be to say flow comes from dealing with “just hard enough” challenges that progress over time with your improving skills.

Experiential Definition of Flow

Flow is an optimal state of consciousness of energized focus and hyper-vigilance.

Flow is an optimal state of consciousness, a peak state where we both feel our best and perform our best. Steven Kotler, The Rise of Superman: Decoding the Science of Ultimate Human Performance

For as much as the operational definition helps us know what induces flow, it’s worth returning to the roots of the concept of flow, peak performance, and classic psychology, since it also must be admitted that flow is an experiential and subjective state. We can and do experience flow. We can and do fall into “The Zone,” a state where time falls away, self-doubt is submerged and our actions, thoughts and bodily motions are smooth and unencumbered. We feel great too.

Flow is largely a subjective experience and a mental state of high concentration and hypervigilance. It is is characterized by profound mental clarity, heightened situational awareness, emotional detachment, and an automatic nature. We don’t think so much as act fluidly and thoughtlessly.

Flow can’t happen when we are distracted, since they take us away from our focus. So an experience of flow requires a relatively distraction-free environment.

Flow also can’t really happen in situations where you don’t feel motivated or care about the tasks at hand. So, to experience flow, you need to be motivated too.

For ages, artists, athletes and performers have described a sense of detachment in what they are doing and even believe they have an intuitive “voice” or “muse” guiding them. They believe they are merely the conduit of these inspired spirits. Essentially in flow we become less self-conscious and simply act.

It was almost as if we were playing in slow motion. During those spells I could almost sense how the next play would develop and where the next shot would be taken. Even before the other team brought the ball in bounds, I could feel it so keenly that I’d want to shout to my teammates, “It’s coming there!”—except that I knew everything would change if I did. My premonitions would be consistently correct, and I always felt then that I not only knew all the Celtics by heart but also all the opposing players, and that they all knew me. —Bill Russell, 1960s basketball legend (quoted in Warren, J. 2009)

There is some debate as to which athlete first called it the “Zone,” but what is flow seems to have gained its greatest foothold in athletics and how these sports performers overcome their self-doubt to perform at their best. The Bill Russell quote could be switched with any number of athletes during their most transcendent performance like Michael Jordan or Simone Biles.

While it might seem like flow is about pursuing peak performance, in fact research into flow has made several interesting discoveries. For example, people who experience flow tend to be happier, both in the moment itself and overall. Flow has been shown as a way to improve learning and accelerate the path to mastery.

Often characterized on an individual level, flow has also been shown to exist in groups, teams and communal situations, like a good conversation, strategizing and product design. Numerous organizations, companies, teams and militaries are all actively integrating flow as a crucial component to improved creativity, elevated performance and greater well-being individually and organizationally.

Flow isn’t a state of rest but a state of doing. Flow is the experience of being so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter. It’s a feeling of energized focus. Flow is an experiential state where you feel focused, confident, energized, motivated and happy in what you are doing.

The short of it is that athletes perform best when their actions are automated, rather than rationally thought out. In fact, cognitively your thinking brain is too slow to be effective in these situations.

The Brain in Flow

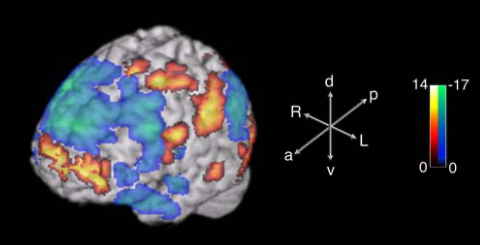

FIGURE 1: Three-dimensional surface projection of activations and deactivations associated with improvisation during the Jazz paradigm. (Limb, 2008)

We now have two working definitions of flow, one that helps us understand what triggers flow (challenging situations that require heightened skills) and one that contextualizes the feeling of flow or “being in the zone” (focused, confident, energized, motivated and timelessly happy).

But what is happening in our brains during flow? What’s the brain like in flow?

Before we dive in, we need to note two things. First, research is still on-going about our brains and flow, and much of what we know about the brain is changing. Second, flow isn’t really a single state but a series or cycle of steps leading up to flow. As such, it is best to characterize multiple brain states before, during and after flow.

In Rise of Superman, Kotler describes the four stages of flow cycle as:

- The “struggle”: The situation facing you is hard. This is the pre-flow stage where you feel challenged and uncertain if you can even accomplish that thing or solve that problem. Examples include problem analytics, physical training, information gathering, intense prayer. It might even involve a good amount of time spent before the activity itself. While a separate topic, these are largely defined as “flow triggers.”

- Release: To transition from struggle to flow, you must pass through a phase of taking your mind off the problem. This might mean going for a walk after a long study or problem-solving session.

- Flow: This is the mental and peak performance stage we previous defined above.

- Recovery: It is impossible to stay in a stage of flow indefinitely. This stage is the return to your normal, rational mind. You likely feel tired out and need time to rest and recover before going back into the challenge-flow cycle.

During the experience of flow (much like creativity and learning), we see several remarkable and distinctive chemical and hormonal patterns in the brain. In the struggle phase, there is an uptick in adrenaline, which is part of flight-or-fight response and primes the body for flow experience. In the release phase, serotonin is released providing positive feeling and reinforcement towards repeating the experience or activity.

The three components of the”flow chain reaction” are:

- Norepinephrine, which is responsible for data acquisition and leads to hypervigilance and focusing, increases.

- Dopamine, which is the often referred to as a feel-good hormone, increases leading to heightened ability to process data and increases our pattern recognition and the fluidity of certain motor skills.

- Anandamide, which is a psychoactive, endogenous cannabinoid (similarly found in marijuana), “elevates mood, relieves pain, dilates blood vessels and bronchial tubes (aiding respiration), and amplifies lateral thinking (our ability to link disparate ideas together).” Anandamide also decreases our ability to feel fear.

As Kotler puts it:

Consider the chain of events that takes us from pattern recognition through future prediction. Norepinephrine tightens focus (data acquisition); dopamine jacks pattern recognition (data processing); anandamide accelerates lateral thinking (widens the database searched by the pattern recognition system).

Aided by this cocktail of neurochemicals, we see profound changes in our brains.

Transient hypofrontality: The Signature Brain State of Flow

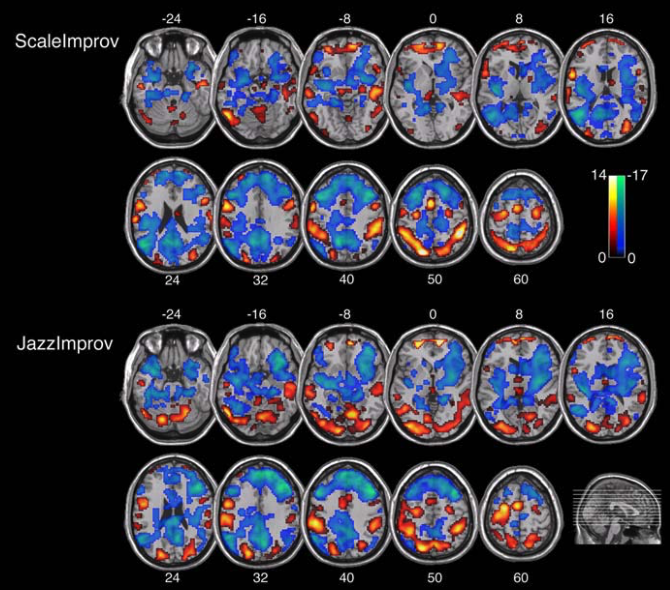

FIGURE 2: Axial slice renderings of mean activations (red/yellow scale bar) and deactivations (blue/green scale bar) associated with improvisation during Scale and Jazz paradigms. In both paradigms, spontaneous improvisation was associated with widespread deactivation in prefrontal cortex…The scale bar shows t-score values and the sagittal section shows an anatomical representation of slice location; both scale bar and sagittal slice insets apply equally to Scale and Jazz data. (Limb, 2008)

Neuroscientists, like Charles Limb (2008) who studied Jazz musicians and freestyle rappers, have found that the superior frontal cortex of brain deactivates when engrossed in certain activities. Similarly, in flow, we see a decrease in brain activity in prefrontal cortex. To put in more colloquial terms, in flow, the “thinking” part of our brains turns off.

Flow creates a state in the brain referred to as transient hypofrontality, which is believed to be the primarily signature of brain in flow. Sitting at the front of brain, unlike our lizard or ancestral brain, the frontal cortex is the “explicit” part of the brain associated with “rationality” and a “personal self.” It is a cognitively slow processing system, compared with the more automated and “self-less” parts of the brain like our cerebellum. It is partially believed to be where aspects of our consciousness and subjective sense of self arise.

During transient hypofrontality our sense of self or self-awareness disappears too. For example, in 2006, Israeli scientists discovered that when people “lose themselves in a task” like playing cards, climbing a mountain or having sex, a part of the brain called the superior frontal gyrus deactivates.

Time dilation is witnessed by those in this state. This is similar to brain scans done on Buddhist monks and Christian nuns by Newberg and D’Aquili who were studying the biology of spirituality and religious belief. During meditation or intense focus, you see orientation association area (OAA) or energy move elsewhere, such that a part of the brain is temporarily blinded. This led them to postulate that the experience of oneness or connection to God is result of this narrowing focus.

Similarly pleasurable and encompassing, flow has often been described by mountain climbers and extreme sport athletes as a oneness in their activity. They describe a transcendent connection with the mountain or an engrossing connection with their tool as a glassblower.

Put another way, on a neurological and subjective level, in flow we stop “thinking” and simply act; our “personal self” disappears and we enact. We are often simply the creative thing we do.

Conclusion: Why Flow Matters

“Don’t ask what the world needs. Ask what makes you come alive. Because what the world needs most is more people who have come alive.”

Howard Thurman, civil rights leader (quoted in The Rise of Superman)

Flow can be defined in two ways: First, on an operational level, we see flow occurs when situations challenge us as the appropriate limit of our skills. Second, on an experiential level, flow is something we subjectively feel as an optimal and even happy state of energized focus and hypervigilance.

While the brain science of flow is still early, a brain in flow reveals a neurochemical cocktail that enlivens our focus, increases our senses and pattern recognition and augments lateral thinking. This leads to what is now referred to as transient hypofrontality, meaning a series of changes associated in the frontal cortex of the brain found in jazz improvisation, meditation and flow.

Now that we know what flow is and the science behind it, it’s worth pausing to ask, why does flow even matter? Put another way, compared to other conceptions of the good life and happiness, why would one want to pursue a life oriented for and around flow?

In my mind, the principal benefits of flow are:

- Attention-Focusing: The mental state of flow leads us to focus our attention on what’s important and what’s matters. The state of flow offers a break from a society increasingly distracted by social media, online videos and a host of activities that pull at and fragment our attention. In flow we feel focused and many of the other benefits emerge from simply being more present and aware.

- Peak Performance: Flow can lead to improved human performance physically and mentally. In his book, The Rise of Superman, Steven Kotler interviews numerous extreme sport athletes, many of who are at the peak of their sport and at the mortal limit of what’s feasible too. Each reveal how flow as a mental state enables them to do what they do from paragliding to big wave surfing. They also reveal how enlivened and happy flow makes them feel too. While many might also be labeled as “adrenaline junkies,” these athletes might be better called “flow junkies” since it isn’t just the risk and fear that drives them, but the heightened state of performance they touch on in while in those moments as well. The short of it is that anecdotal and some research evidence shows that flow makes us perform at a higher capacity than otherwise. So if you wish to push your creative, physical or even learning goals, flow is a key mental state to pursue too.

- Energizing: Flow requires and leads to an energized state. From tracking and experimenting with flow, I’ve come to realize a strong connection between flow and feeling energized. It is a two-way street. Flow does increase how energized and focused I feel. But in order to get into flow I need to feel energized and capable too. That means getting enough sleep, eating well, and avoiding too much negative stress allow me to be energized and get into flow.

- Superpowers our Learning and Skill-Building: The various neurochemical and subjective mental changes result in state of mind that learn faster and exponentially increase the rate of developing and honing our skills. Research has shown that flow accelerates the pace of learning. Learning can be a struggle, but a looking at how we learn reveals that the struggle before flow results in an optimal state in flow where we build new powerful connections and lasting memories.

- A Positive State of Stress in Flow = Happiness: I’ve personally struggled with defining what is happiness and I am not convinced that happiness should be the guiding thread in my own life philosophy. Stress is often framed negatively, but there is an upside to certain kinds of stress and how we respond to it. Specifically, our response to stress offer a chance at a positive and healthy answer to challenges around us. Instead of closing down and panicking as we deal with challenging tasks at hand, the experience of flow can be thought of as a positive form of stress (sometimes called eustress). These positive responses help us to build resilience and a sense of accomplishment. Flow itself is highly enjoyable and, as flow researchers like Csikszentmihalyi have shown, they make us happier and increase life satisfaction.

- Less Self-Conscious, Increased Creativity and Problem-Solving: From looking at the brain in flow, we see a marked deactivation of our prefrontal cortex normally associated with higher rational functions, like planning and self-monitoring. Experientially flow translates to a state where we are “less in our head,” meaning we judge ourselves less critically and are less self-conscious. Somewhat ironically, these brain changes, peak performance benefits and improved rate of learning augment our capacity to be more creative. From studies on artists, athletes, musicians and more show that flow makes us not only feel more creative, but in fact, our creative outcomes are better too. Facing hard problems at the limit of our ability to deal with them isn’t really pleasurable per se, but this experience of being creative during flow are ultimately enjoyable, since situations that induce flow pull at our minds and bodies leading us to enact our own most creative responses possible. In short, they make us feel more alive and meaningful and subsequently more creative too.

As a long-time self-tracker, quantified self enthusiast, and biohacker, I often look for trackable metrics to orient how I understand and improve my life. Among other things, I look at health data to help me better understand what makes me feel more energized, sleep better, and avoid lifestyle diseases, and I study my time tracking data, calendar and tasks completed to know where my time and attention goes and decide what goals I should do. It has even help me optimize certain tasks and goals for certain times of day.

In the past I’ve even turned to mood tracking as a way to quantify how I feel in general and at certain points of the day. Mood tracking has failed me in the past since it’s a pretty limited slice of what matters in a life, namely how you feel. Obviously depression or a bad mood will severely impact your ability to be productive or creative, and we should strive to prevent these negative baseline mental states. But just “not being sad” doesn’t offer a framework for fulfilling life either, nor does the singular pursuit happiness or pleasure either.

Compared to happiness or mood, flow offers a more complex and enriching path towards human flourishing. Increasing flow in a life tends to be beneficial in so many areas. Flow can improve performance, enjoyment, energy level, creativity, happiness, learning, problem-solving and more. These benefits have lead me to design aspects of my life around flow and expand my tracking to include flow and related subjective metrics, like motivation and how energized I feel. I’ll leave the the topic of tracking flow for a future post. But we should never forget that flow doesn’t happen when the task at hand is easy. Tasks that are too easy bore us. Tasks that are too hard scare and intimidate us, leading us to stress out and panic.

To reach a mental state of flow we need to be challenged, often times at the very limit of what we are capable and where we will sometime fail. Put another, while a life of flow has many benefits and I personally believe it is a life worth living, it doesn’t and can’t occur unless we are pushing ourselves at the very limit of what is possible. Living in and for flow may be enjoyable but it isn’t easy.

References:

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2008). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience (Harper Perennial Modern Classics) (1 ed.). Harper Perennial Modern Classics.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1997). Finding flow: The psychology of engagement with everyday life. Basic Books.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention (56). New York: Harper Collins.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Larson, R. (2014). Validity and reliability of the experience-sampling method. Flow and the foundations of positive ….

- Hektner, J. M., Schmidt, J. A., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2007). Experience Sampling Method. SAGE.

- James, W. (1902, 2014). The Varieties of Religious Experience. Masterlab.

- Kotler, S. (2014). The Rise of Superman. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Limb, C. J., & Braun, A. R. (2008). Neural substrates of spontaneous musical performance: An fMRI study of jazz improvisation. PLoS one, 3(2).

- Nakamura, J., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2009). Flow theory and research. Handbook of positive psychology, 195-206.

- Newberg, A., & d’Aquili, E. G. (2008). Why God won’t go away: Brain science and the biology of belief. Ballantine Books.

- Newberg, A. B., & d’Aquili, E. G. (2000). The neuropsychology of religious and spiritual experience. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 7(11-12), 251-266.

- Newberg, A., Alavi, A., Baime, M., Pourdehnad, M., Santanna, J., & d’Aquili, E. (2001). The measurement of regional cerebral blood flow during the complex cognitive task of meditation: a preliminary SPECT study. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 106(2), 113-122.

- Warren, J. (2009). The Head Trip. Vintage Canada.