From self-help gurus to pop psychologists, one message seems clear and nearly ubiquitous: “Be true to yourself.” Today the pursuit of authenticity has woven itself into the fabric of our culture and is championed by influential figures like Oprah Winfrey, Dr. Phil McGraw, and Deepak Chopra. Each encourages us to “unearth” our true selves, emphasizing that each of us possesses an “inner self” and unique personal identity that we need to and should express as our own.

But what is the nature and characteristics of such a authentic self? And why do so many gurus want us to pursue and base our life choices upon it?

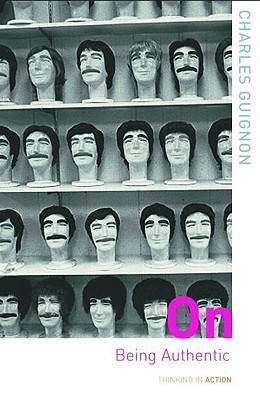

It’s undeniable that we live in a society that places a premium on being an authentic individual. But such an assumed life ideal has a relatively recent history coming out of 17th Century Europe. In “On Being Authentic,” Charles Guignon take a critical look at the history and philosophical foundations of authenticity.

According to Guignon, we should be skeptical of self-help gurus since, as he puts it, “Ironically, programs that are designed to help people get in touch with their true selves, supposedly motivated by emancipatory ideals, often have the effect of pressuring people into thinking in ways that confirm the ideology of the founders of the program.” Quite simply, pop psychology and self-help gurus aim at you finding a self that they just so happen to believe they can sell something for.

Beyond mere contemporary examples, authenticity also carries with it the legacy of a dramatic and important cultural shift in how we think and understand what it means to be a self. Guinon asks:

“What if the whole notion of the innermost self is suspect? What if it turns out that the conception of inwardness presupposed by the authenticity culture, far from being some elemental feature of the human condition, is in fact a product of social and historical conditions that need to be called into question?”

In this cultural transition, individuals were uprooted from a social framework defined by roles and a place in the greater cosmic order, and the modern notion of a self defined “innerwardness” was born. In his book, Guinon considers:

- What is the legacy of such a framing of a certain kind of authentic self?

- And can we formulate an alternative, a more authentic, authentic self?

As a thinker and technologist, I’m in the process of both writing and reading about the conept of authenticity, namely how to define it, what are the characteristics of an authentic self and why does it matter to us as individuals and communitities of meaning? Hopefully by grounding a sense of our authentic self, we can start to live accordingly. Beyond just the philosophical and personal questions, I’m keen to explore how such a concept fits in the age of Artificial Intelligence (AI). For example, how might we live authentically while also engaging, learning and creating with such tools as ChatGPT?

As we consider what lives are worth living and how to answer for ourselves and our societies what it means to find and express our authentic selves, let’s take a look at one author’s take on the many perspectives and historical origin behind authenticity.

Here are my book notes and a few of my takeaways and lessons.

Book Notes, Quotes and Key Takeaways for “On Being Authentic” by Charles Guignon

- Authenticity has become integral to pop psychology and the self-help industry, and in fact, “it could be argued that the ideal of authentic existence is absolutely central to all the movements that make up the self-improvement culture” (p vii). Consider figures such as Ophrah Windrey, Dr Phil McGraw or Deepak Chopra’s “here to discover our true Self” and that each of us has “a unique talent and a unique way of expressing it.”

- English philosopher Bernard Williams, “If there’s one theme in all my work it’s about authenticity and self-expression, It’s the idea that some things are in some real sense really you, or express what you are, and others aren’t.”

- Moral perfectionism: Expressed in Emerson, Nietzsche and Cavell, the American philosopher Russell Goodman defines “moral perfectionism” as an approach to moral philosophy “in which the idea of the individual being true to, cultivating, or developing him- or herself occupies a central place.”

- Finding God/Devine in Your Authentic Self: Authenticity can be expressed as finding God “in the deepest and most central part of thy soul” according to early seventeenth-century theologian and mystic, William Law.

- Two components to the ideal of authenticity:

- Find your true self: “Get in touch with the real self we have within, a task that is achieved primarily through introspection, self-reflection or meditation. Only if we can candidly appraise ourselves and achieve genuine selfknowledge can we begin to realize our capacity for authentic existence.”

- Express your true self, i.e. “ideal calls on us to express that unique constellation of inner traits in our actions in the external world—to actually be what we are in our ways of being present in our relationships, careers, and practical activities. The assumption is that it is only by expressing our true selves that we can achieve selfrealization and self-fulfillment as authentic human beings.”

- Tension between two components because the first “concept of authenticity is an ideal of owning oneself, of achieving self-possession” (which Guignon labels “enownment” and can be pithily expressed as “Be all that you can be”) while the second demands self-loss or releasement such that the “highest goal in living, on this view, is to become a new person by becoming responsive to the call of something greater than yourself.”

- Examples of this “something greater”: God’s will, social solidarity and reform, the sanctified callings of ordinary life, the cosmic order of things, or even “Being” (the philosopher Heidegger said that humans are the “shepherds of Being”). The suggestion here is that we should seek release from the bondage to ego, not ever greater involvement in the “I.”

- Self-Help gurus aim at you finding a self they can sell to: “Ironically, programs that are designed to help people get in touch with their true selves, supposedly motivated by emancipatory ideals, often have the effect of pressuring people into thinking in ways that confirm the ideology of the founders of the program.”

- Critical Question: “What if the whole notion of the innermost self is suspect? What if it turns out that the conception of inwardness presupposed by the authenticity culture, far from being some elemental feature of the human condition, is in fact a product of social and historical conditions that need to be called into question?”

- Authenticity is a function of acting on that authentic self: “Self-knowledge is therefore a first step not toward “being yourself” as we understand it, but toward a project of excising what is particular and distinctive in yourself in order to be better able to match the ideal that determines your function.”

- Pre-Modern “inward and upward” search: St Augustine’s introspective search wasn’t a modern one centered on authenticity or even a self, instead “what Augustine finds through his self-inspection is that the self is like a free radical, incomplete and hopelessly unstable unless it is bound in the right way to God.” “We turn inward only as a means to making contact with and relating ourselves to the Being through whom we first come to be and at any time are. Where Socrates’ vision of reality was cosmocentric, Augustine’s is theocentric.”

- Extended Self of Pre-Modern Human Societies: “The self is experienced as what sociologists call an extended self: my identity is tied into the wider context of the world, with the specific gods and spirits that inhabit that world, with my tribe, kinship system and family, and with those who have come before and those who are yet to come. Such an experience of the self carries with it a strong sense of belongingness, a feeling that one is part of a larger whole.”

- “Religious individualism” = “the absolute centering of the question of religious life on the individual”

- Michel Foucault: “subjects of inwardness.”

- We tend to “psychologize” issue of living with a pervasive concern with our “inner self.”

- “The modern outlook brings to realization a split between the Real Me—the true inner self—and the persona (from the Greek word for “mask”) that one puts on for the external world.”

- For Freud, our Id is the Real Me or authentic self “upon whose surface rests the ego.”

- Self in Modernity defined as “bounded, master self” or “sovereign self” (Joseph Dunne)

- Post-Modernism argues for the “de-centered subject” leading to a view of the self as polycentric, fluid, “contextual subjectivities.” Furthermore, selves possess “limited powers of action, choice, and multiple centers with diverse perspectives.”

- Freedom enables pursuit but doesn’t answer question of what or why: “In our actual experience, freedom strikes us as valuable not because it is an end in itself, but because it enables us to pursue and achieve the things we regard as genuinely worth having…Freedom is essential to our modern image of ourselves as self-defining subjects. But when it comes to deciding which course of action we should pursue, it does not seem to provide much direction…Freedom in turn is regarded as the ability to pursue happiness as one sees fit. Happiness and freedom are the privileged goals of living according to the modern outlook”

- “To many it became evident that modernity engenders a way of life characterized by obsessive pursuits that lead to alienation not only from others, but from one’s own self as a human being with feelings and needs. While the modern worldview opened doors to previously unimagined possibilities of human activity and selfresponsibility, it also tended to undermine the ability to formulate a coherent, viable image of the ends of living.”

- Rousseau writes in his Confessions: “I have only one faithful guide on which I can count: the succession of feelings that have marked the development of my being…. I may omit or transpose facts, or make mistakes in dates; but I cannot go wrong about what I have felt or about what my feelings have led me to do; and these are the chief subjects of my story.”

- Romanticism: “for Romantic thinkers, getting in touch with nature is seen as only an initial step on a longer path that leads to an even higher level of insight and realization. For the true goal of the Romantic quest is spiritual autonomy, and in relation to this goal the experience of oneness with nature is merely a preliminary stage. The self must pass through a stage of thinking that it is one with nature and that this is the highest truth, but this is only a transitional stage, a stage that itself will be surpassed as the mind reaches a yet higher truth. The ultimate destination is the recognition of the absolute priority of the creative powers of the human imagination over both the natural self and nature. At the culmination of the Romantic quest, organic energy is superseded by creative energy. Romanticism aims not at humanity’s oneness with nature, but at the ultimate humanization of nature in the apotheosis of human creativity.”

- “The authentic self is the individual who can stand alone, shedding all status relations and social entanglements, in order to immerse him- or herself in “sheer life.””

- Binary Oppositions “give us a sense of how things are organized in the world. Without being aware of it, we employ sets of contrasting terms in which each term is defined by its contrast with the opposing term, for example, up/down, front/back, left/right, tall/ short, fat/thin, and light/dark. These oppositions articulate and organize the conceptual field in such a way that our perceptions and interpretations tend to follow certain clearly demarcated paths.”

- “The binary oppositions governing our thought lead us to see the natural side of life as pure, spontaneous, and innocent, whereas the social or public side of life is seen as calculating, contrived, tainted, and so deformed and fallen.”

- “These conceptual oppositions in turn map onto the distinctions we make between deep vs. superficial, spiritual vs. materialistic, organic vs. mechanical, genuine vs. fake, true vs. illusory, and original vs. simulation. Sets of binary oppositions lead us to see various contrasts as tied in to others. It is also the nature of binary oppositions that they are ‘valorized’ in the sense that the terms making up the oppositions are perceived as ranked in such a way that one term of the pair is regarded positively, as referring to something regarded as good or proper, while the other term is regarded negatively, as referring to something derivative or even decadent and degenerate.”

- “Most of us deal with the conflicting demands made on us in the modern world by being instrumentalists in public and Romantics in private.”

- Master dichotomy of inner and outer: “It could be argued that in the modern period the master dichotomy governing all others is the opposition between inner and outer. It seems natural to us to suppose that, with respect to the self, what is inner is what is true, genuine, pure, and original, whereas what is outer is a mere shadow, something derived, adulterated and peripheral.”

- Anthony Giddens: the “invention of childhood.”

- Swiss psychoanalyst Alice Miller - “child as the “true self” and “valorization of the infant’s experience over the adult’s” in The Drama of the Gifted Child: The Search for the True Self

- “a pervasive concern with the inner self”

- “To be human, according to the modern way of thinking, is to be a subject, a sphere of subjectivity containing its own experiences, opinions, feelings and desires, where this sphere of inner life is only contingently related to anything outside itself.”

- “The subject is defined as an “inner space”—it is a mind or field of consciousness containing such mental contents as perceptions, interpretations, memories, feelings, desires, goals and needs. Its relation to the “outer,” material world is mediated by those mental contents (e.g., the sensations received through the senses and the actions”

- Critique of essentialism, i.e. “belief in the substantial “I” begins to look dubious”

- Which self am I most truly: “Am I a teacher who dabbles in music or a musician trying to make ends meet by teaching?”

- Nietzsche: “The assumption of one single subject is perhaps unnecessary…perhaps it is just as permissible to assume a multiplicity of subjects, whose interaction and struggle is the basis of our thinking and our consciousness.”

- William James: “a man has as many social selves as there are individuals who recognize him.”

- Clifford Geertz: “man is, in physical terms, an incomplete, an unfinished animal;… what sets him off most graphically from nonmen is less his sheer ability to learn (great as that is) than how much and what particular sorts of things he has to learn in order to function at all.”

- “Our identity is something that comes to us already made by our culture.”

- Monological consciousness

- Dialogical Self - “The conclusion to draw from the dialogical nature of experience is that we experience the world through a “We” before we experience it through an “I.”

- “We are at the deepest level polyphonic points of intersection with a social world rather than monophonic centers of self-talk and will. For this reason, we generally come to have a better knowledge of who we are through our social interactions than we do through introspection or self-reflection.”

- “We appear to be caught in a dilemma. Either we see the self at the core of dialogical interchanges as a continuous, enduring self, in which case we resurrect the modern individual. Or we see the self as a transient “stand taken in the present moment,” one stand among many, in which case we seem to come back to the disjointed, dispersed self of postmodernism.”

- Narrativist View of the Self: Self might be like a story such that “we have the ability to shape an identity for ourselves by taking over those social interpretations in our active lives and knitting them together into a unique life story.” / “continuous, ongoing, open-ended activity of living out a story over the course of time. It is this narrative unity and continuity that defines the “I.”” / “we are not just tellers of a story, nor are we something told. We are a telling.”

- “the self is something we do, not something we find. We are self-making or self-fashioning beings”

- “In our actual experience of our lives as agents, what has priority is the future, where the future is understood as an open realm of aims and ideals that guide us and give our actions a point. It is the open range of possibilities for the future that lets past come alive and mean something to us. We experience the past as a set of resources carried forward in achieving what we hope to accomplish. Finally, the present is experienced not as the one truly existing time, but rather as a point of intersection between future and past, the context of action in which purposes can be realized thanks to what is made accessible from the past.”

- “Life is therefore an open-ended and inconclusive project.”

- “This long excursion through narrativist conceptions of the self leads us to a way of thinking of authenticity not as a matter of being true to some pregiven attributes of an antecedently given, substantial self, but instead as a matter of finding and coming to embody a set of defining commitments that first make us into selves. To be authentic, on this account, is to take a wholehearted stand on what is of crucial importance for you, to understand yourself as defined by the unconditional commitments you undertake, and, as much as possible, to steadfastly express those commitments in your actions throughout the course of your life. What shapes your identity, according to this picture, is determined by what you identify with: the life-defining ideals and projects that make you who you are.”

- As Nietzsche says, “In the end, when the work is finished, it becomes evident how the constraint of a single taste governed and formed everything large or small. Whether this taste was good or bad is less important than one might suppose, if only it is a single taste!” (GS §290).

- “The project of being authentic” has two components:

- “First, there is the task of pulling yourself back from your entanglements in social game-playing and going with the flow so that you can get in touch with your real, innermost self. This task requires intensive inward-turning, whether such self-inspection is called “introspection,” “selfreflection,” or “meditation.” The assumption underlying the first component of the project of being authentic is that there is a substantial self lying deep within each of us, a self with attributes that are both distinctively our own and profoundly important as guides for how we ought to live.”

- “The second component of the project of authenticity involves living in such a way that in all your actions you express the true self you discovered through the process of inward-turning. The assumption here is that there is something fundamentally false or dishonest about social life, and for that reason it is crucially important to know who you are and be the person you are in all you do.”

- Is the pursuit of an authentic life worth pursuing?: “Given the dangers involved in the project of authenticity, we might ask why we suppose that authenticity is a good thing. Why should anyone even want to be authentic? The first temptation is to see this question as absurd, like asking, Why should anyone ever want to be happy? But unlike happiness, authenticity is not a condition that is obviously good in itself. Most people would agree, I think, that becoming and being authentic is an arduous process, and that authentic people are not necessarily the happiest people in the sense of having pleasurable feelings most of the time. The ideal of authenticity makes a very heavy demand on you, one that outweighs concerns about sustaining good feelings in all situations.”

My Quick Take Book Review: “On Being Authentic” by Charles Guignon

Compared to a couple recent books I’ve read on authenticity, Charles Guignon’s On Being Authentic was the easiest to read and offered the clearest and shortest introduction to key philosophical topics related to authenticity. Guignon’s book inherits many of the same questions and core reason as Charles Taylor’s The Ethic of Authenticity (check out those books notes here), and you might consider this book as a sharper introduction of similar themes.

- I rated this book a 5 out of 5 on Goodreads.

- Would I recommend it? Beyond the mere philosophically inclined, I would definitely recommend this book. This book is a great primer on key history of this concept and it frames the core questions about how we conceive of a life worth living.

- Would I read it again? I think I would pick up this book again, though not likely in the short-term.

I particularly liked the intro and overall framing based on the role authenticity plays in self-help and personal development space. Authenticity is an important operational concept behind what gurus and self-help writers are trying to sell so it’s a concept worthy of a critical appraisal. His examples and grounding are clear and well-articulated. He tends to get caught up in diving into the weeds on certain threads, though I’d admit that I quite enjoy those asides.

What I got out of this book?

Three core ideas resonated with me in this book.

How Pre-Modern Frameworks Defined Our Place and a Self

I’ll admit that I hadn’t previously considered the historical origins of authenticity since it seemed to quite similar to the Greek notion find in Socrates to “Know thy self.” For Plato, knowlege of self was largely an epistemological turn and not formulated in terms of a personal identity.

For Guinon, the concept of authenticity, as we understand it today, sits on deeper historical roots, primarily stemming from the era of Modernism, notably the Enlightenment and Romanticism. According to Guignon, this is best understood in contrast with two older paradigms:

1. The Extended Self in Pre-Modern Human Societies

In pre-modern human societies, individuals were perceived as integral components or extensions of the collective whole. Personal identity was deemed to be an extension of a social order or so-called “Great Chain of Being.” Individuals derived their sense of purpose from their roles within society and the narratives and myths that imbued them with a sense of place. In this worldview, individuals existed primarily as part of a greater societal and cosmic narrative, with their individuality subordinate to this overarching framework. Who they were individually was largely who they were collectively.

2. The “Inward and Upward” Quest for Self, Tied to the Divine

One the surface, Augustine of Hippo or St. Augustine’s Confessions, which was written around 400 AD, seems to be quite a modern take on the self and could be read in terms of authenticity. Augustine’s Confessions makes an important new literary genre, but a more critical take would appear to show that Augustine’s introspective journey differed significantly from the modern pursuit of authenticity or self-realization. Rather than seeking an authentic self, Augustine embarked on an inward odyssey to establish a profound connection with the Divine. By searching inward, he didn’t find an inner self as we define; he found the Divine or God.

For Guinon, Modernity and the Enlightenment led to a dramatic shift in how we understand ourselves and our place in the universe. The Divine, the cosmic order or an “extended self” were no longer answers to the meaning of life. Instead, the scientific revolution and rise of individualism in political philosophy and modern societies shifted the nexus of meaning and agency to the subject.

Two Deeply Opposed Conceptions of Life

This revolution also led to one of the more important points in the book and one that particularly resonated for me. For Guinon, we have yet to find a complete replacement for the loss of these previous foundations for personal meaning and larger collective narratives for individuals. “What criteria should we base our lives and societies on?” remains an open question and has led to what he calls “two deeply opposed conceptions of what life is all about.”

- Rationality Perspective - Backed by science, this position argues that our lives and societies should be guided by procedural logic and science. Following the success of science and engineering in explaining and transforming the physical world, rationalists believe we should apply the same logic, rules and reasoning to our personal and social lives. Decisions about what and how to live better can and should be answered rationality and instrumentalist interpretations.

- Romantic orientation - This counterforce rejects a life framed and decided purely on instrumental and utilitarian terms. Heralded by French Philosopher Jean-Jacquer Rousseau, who could be argued to be one of the first expressions of modern authenticity (though he never used the word itself), Romantics champions a return to nature, not as a physical retreat, but as a profound reconnection with the self. Guinon posits that for Romanticism the “ultimate destination is the recognition of the absolute priority of the creative powers of the human imagination over both the natural self and nature.” In this paradigm, the human subject, the self, emerges as the focal point, standing supreme over both the natural self and the external world. What matters is to be a free, self-defining entity.

I believe this schism or “binary” between the rationalist and romantic orientations underscores a fundamental tension that continues to shape contemporary discussions and choices. These opposing worldviews reverberate across diverse aspects of society and even our own personal identities and our pursuit of the authenetic life. In a remarkable passage, Guinon points out that, “Most of us deal with the conflicting demands made on us in the modern world by being instrumentalists in public and Romantics in private.” Put another we navigate these two poles of authenticity by taking on a practical job and role in the public sphere, while maintaining hobbies, side hustles and interests in our private sphere.

This leads to the third major point that resonated with me.

Finding Authenticity Amidst Value-Loaded Binary Oppositions

These splits between an private/public or inner/outer self are just one of many what Guinon terms “binary oppositions,” which are contrasting terms we use to “give us a sense of how things are organized in the world.” For example, in a conventional sense, “we employ sets of contrasting terms in which each term is defined by its contrast with the opposing term, for example, up/down, front/back, left/right, tall/ short, fat/thin, and light/dark.” These oppositions delineate and structure our perceptions and thinking, leading to interpretations that adhere to specific, well-defined contrasts or oppositions.

In most cases, they are simply expressions of contrasts, but in some cases these oppositions delinate underlying values too. A classic example is the opposition between natural and public sides of life, wherein the “the natural side of life [is] pure, spontaneous, and innocent, whereas the social or public side of life is seen as calculating, contrived, tainted, and so deformed and fallen.”

To follow this thread one step forward, “These conceptual oppositions in turn map onto the distinctions we make between deep vs. superficial, spiritual vs. materialistic, organic vs. mechanical, genuine vs. fake, true vs. illusory, and original vs. simulation. Sets of binary oppositions lead us to see various contrasts as tied in to others. It is also the nature of binary oppositions that they are ‘valorized.’” Romantic vs Rationalist perspective is an example of a value-ladden binary opposition.

Value-Loaded Binary Oppositions play a crucial role in shaping how we perceive the world. These oppositions create a framework in which one term of the pair is typically regarded positively, associated with what is considered good or proper, while the other term is seen negatively, often linked to something derivative or decadent. In essence, binary oppositions influence our value judgments and guide our understanding of various aspects of life.

It’s important to recognize that the foundational concepts of authenticity today are also enmeshed within these sets of binary oppositions. To be perceived as inauthentic within this framework is akin to being labeled as fake or superficial, and to be authentic is, according to its binary pole, to be true and real, similar through these value-embedded contrasts.

Value-loaded binary oppositions raise several intriguing some question about authenticity in contemporary society. What criteria can we use to differentiate authenticity from inauthenticity in a world where these binaries hold sway? Are there instances where authenticity can transcend or redefine these oppositions? How does our pursuit of authenticity intersect with our broader cultural value systems we are a part of and help to define?

Got a comment? Send me an email.

References:

- Guignon, C. B. (2004). On Being Authentic. Psychology Press.